Mismap = Misuse

|

| circle vs ellipse |

Compare the pictures below.

|

| femoral head = sphere |

|

| source |

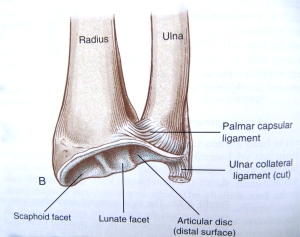

radiocarpal joint

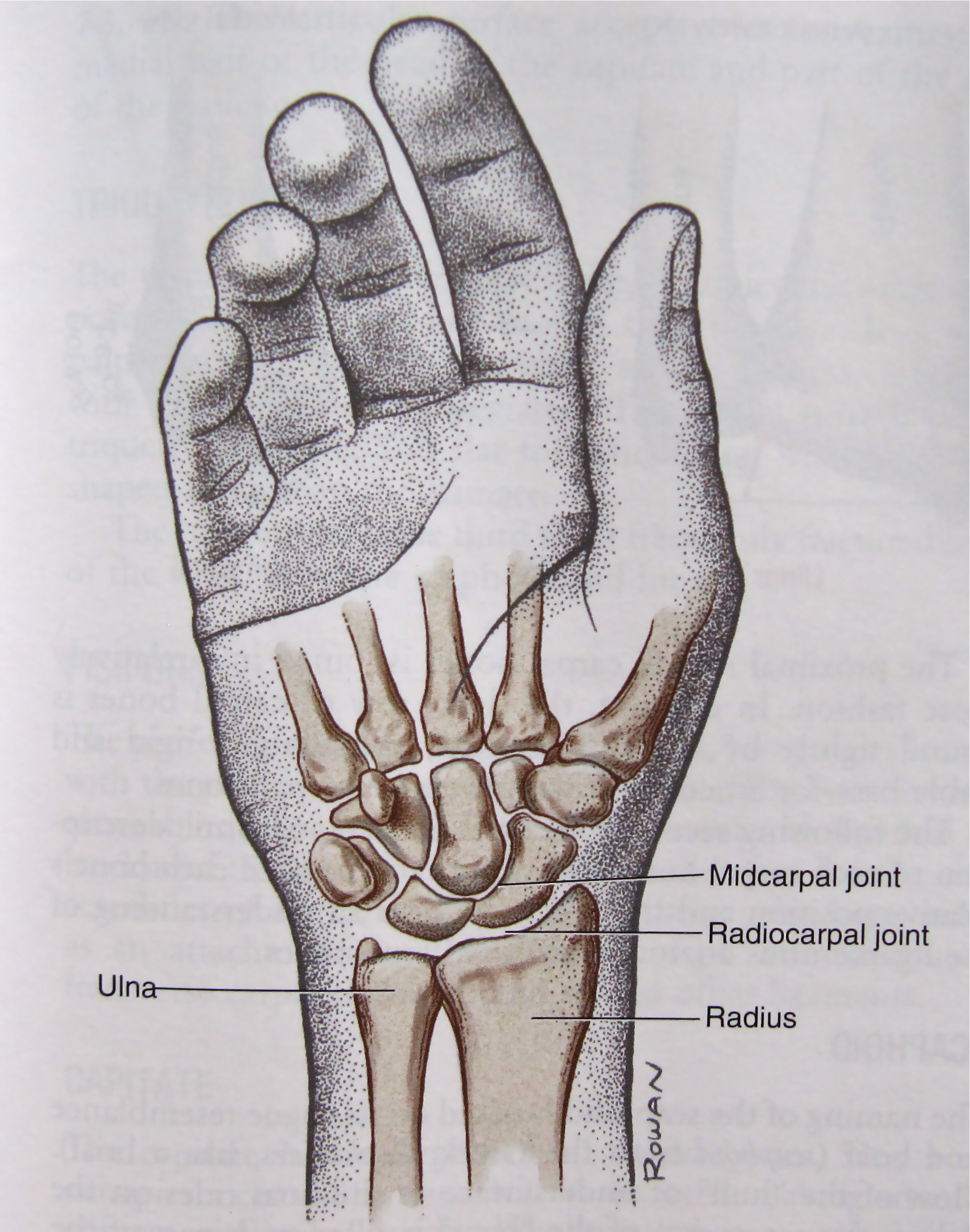

These drawings of the anterior view of the right hand (palm side) show that the wrist is articulated by several bones: the radius and carpals. Though the ulna parallels the radius in the forearm, it merely provides elliptical movement for the wrist, made possible by ligaments.

|

| source |

If both the radius and ulna ended closely to the carpals, our hands would basically move in one direction, like a door opening and closing. The flexibility we need to play marimba, multi set-ups, drumset, and just about everything else is made possible by the space between the ulna and carpals.

Soft tissues fill that space in the form of ligaments, tendons, muscles, and blood vessels, and there will be more about them in a future post. :)

This leads us, as percussionists, to a very important concept, demonstrated in the video below.

Video not working? Click here.

movement

The two primary planes of movement, grouped as flexion and extension, and adduction and abduction, respectively, dictate how we can best approach playing in order to prevent injury.Notice that the field of possible motion for flexion and extension is quite large compared to that for adduction and abduction. This explains, to a great extent, why nearly every technique is based on some mix of flexion and extension: there are simply more possibilities, more opportunities for specificity, and, due to more muscle support, greater control.

Some techniques, like French grip on timpani, rely on adduction and abduction, but the sound desired from the grip correlates to having less power and less range of motion: lightness, bounce, percolating energy.

There is something to be said about the alignment of the fingers and health of the wrist, even in flexion and extension.

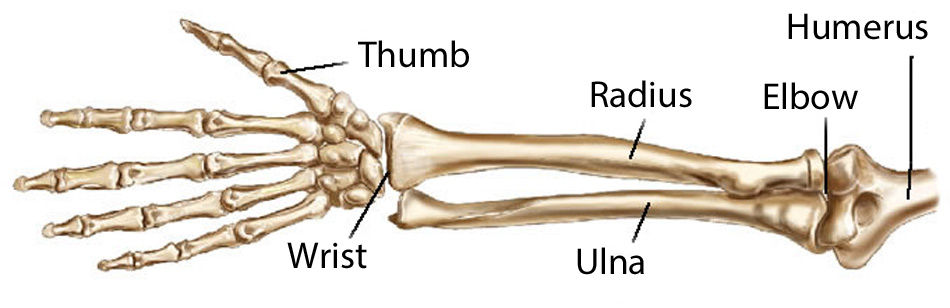

Check out the diagram below. It shows a continuous arced line from the elbow, through the radius, to the tip of the middle finger. The wrist's axis is most supported along this arc.

|

- Centering the thumb would require constant adduction, and compression of the space between the ulna and carpals.

- Centering the index finger would require slight adduction, causing tension in the upper forearm near the elbow.

- Centering the fourth or fifth fingers would require extreme constant abduction, resulting in pain at the center of the wrist.

With hindsight has come clarity about one of my own alignment missteps about five years ago.- Centering the fourth or fifth fingers would require extreme constant abduction, resulting in pain at the center of the wrist.

A Brief Testimonial

In summer 2011, once out of school but still pushing myself in practice sessions, I developed a strange torque in my left wrist. In my efforts to align my outer mallet with my forearm I constantly abducted my wrist, thinking that my pinkie should be in a straight line with my forearm, not at an angle.

Eventually a dull pain developed at the top of my wrist, where a watch would be. I wore a brace at night maybe once or twice a week, and other than that all was fine. At least, until preparing for a performance at the Zeltsman Marimba Festival in Appleton, WI. While playing a fast, awkward run, there was a loud *pop* from my left wrist and immediate immobility.

Terrified, I called my doctor (aka, my mom), and explained what happened - that it felt like my tendons just popped over one another and now wouldn't move. She assured me that it would move again, probably in a few minutes, but that I was maybe dealing with the beginnings of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

People in my family have had surgery for it, and never recover full strength after, so her words were terrifying to hear. I could NOT be 25 with Carpal Tunnel, not if I was going to keep playing.

Through research I learned that I was aligning the wrong finger, and should have focused on my middle finger, as shown in the diagram above. Once I figured this out, it only took a few weeks of mindful practice to get rid of it. And, perhaps most excitingly, years later my chops are better, my tempos are faster, and my adventurous side has been able to experiment with adaptations that before would never have worked for me, like the Corrente from BWV 830.

I still mindfully practice, and still slowly investigate my own alignment.

It has become a joyful part of my practice.

Up Next

To further clarify these ideas of alignment, I will make a video showcasing ways to discover your own tendencies, get familiar with your wrists, and investigate your technique for potential injury-causing habits.

I will release it before the end of the month, so stay tuned!

- - - - - - -

Bruce MacFarlane, MD. "Notes on Anatomy and Physiology: The Elbow-Forearm Complex." written Oct 2010, accessed March 2016.

Great tips regrading bones and joints. You provided the best information which helps us a lot. Thanks for sharing the wonderful information.

ReplyDeleteGet the best health, gym, sports, beauty products and more delivered to your doorstep at low prices.

ReplyDeleteBuy Wrist and Forearm Splint with Thumb Supporter